Is Dysbiosis the Missing Link in Type 1 Diabetes?

- admin

- October 6, 2024

- 8:40 am

- No Comments

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) has always been seen as a battle between the immune system and insulin-producing cells.

While genetics and environmental triggers like infections have been discussed at length, recent research is exploring a less obvious culprit—dysbiosis.

Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the microbial community in our gut, which is increasingly linked to autoimmune diseases, including T1D.

The gut is not just a digestive organ, but a hub that communicates with our immune system and metabolism.

So, is dysbiosis the missing link that could explain how type 1 diabetes develops?

Article Index:

- Understanding Type 1 Diabetes: A Quick Overview

- What is Dysbiosis and How Does It Happen?

- Gut Health and Immune Response: A Delicate Balance

- Scientific Evidence: How Dysbiosis and T1D Are Connected

- Daily Lifestyle Factors That May Trigger Dysbiosis

- Can We Predict Type 1 Diabetes Through Dysbiosis?

- Conclusion: Is Dysbiosis the Missing Link?

Understanding Type 1 Diabetes: A Quick Overview

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas.

This results in a lifelong dependence on insulin injections to regulate blood sugar.

Most cases develop in childhood or early adulthood, although it can emerge at any age.

The exact cause of T1D is still unknown, but it’s generally accepted that a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors plays a role.

However, the recent spotlight on gut health suggests another layer of complexity—dysbiosis.

What is Dysbiosis and How Does It Happen?

Dysbiosis is a term used to describe an imbalance or disruption in the gut microbiome—the vast and diverse community of microorganisms living in our intestines.

This microbial community is essential for breaking down food, producing vitamins (like B12 and K), training the immune system, and even influencing mood through the gut-brain axis.

Under healthy conditions, beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium keep the gut environment in check.

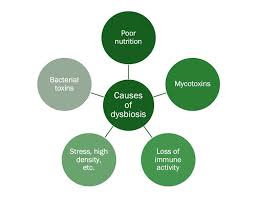

But when this balance is disrupted—due to factors like high-sugar diets, stress, lack of dietary fiber, or prolonged antibiotic use—the gut enters a state of dysbiosis. This allows opportunistic or harmful microbes like Clostridium difficile or Escherichia coli to flourish.

Scientific studies from journals like Nature Microbiology and Cell have shown that dysbiosis can lead to a “leaky gut,” a condition where the intestinal lining becomes permeable. This allows toxins and bacteria to escape into the bloodstream, potentially triggering systemic inflammation.

Chronic inflammation, in turn, has been linked to a host of conditions ranging from obesity and chronic stress backed type 2 diabetes to autoimmune diseases like type 1 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

For example, in one mouse model study published in Diabetes, a dysbiotic gut microbiota was shown to accelerate the onset of autoimmune diabetes by promoting a pro-inflammatory immune response.

Similarly, people with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) often show reduced microbial diversity, especially a lack of anti-inflammatory species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii.

Even common issues like bloating, gas, diarrhea, or fatigue may be early signs of dysbiosis. To restore balance, interventions such as a fiber-rich Mediterranean diet, fermented foods, prebiotic supplements, or even fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) have been researched and shown to help reestablish a healthier gut environment.

In short, your gut isn’t just digesting your lunch—it is managing your entire health story.

Gut Health and Immune Response: A Delicate Balance

Our gut acts as a mediator between the outside world and our immune system.

Around 70% of the body’s immune cells reside in the gut, and they constantly interact with gut microbes.

The balance between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bacteria is crucial to maintaining immune tolerance—meaning the immune system knows when to attack and when to stand down.

In cases of bacteria dysbiosis, the immune system may overreact to harmless gut bacteria, setting off an inflammatory cascade.

This could potentially lead to the misfiring of immune responses, as seen in T1D, where the immune system attacks pancreatic beta cells.

Scientific Evidence: How Dysbiosis and T1D Are Connected?

The connection between dysbiosis and diabetes, particularly type 1, is still being researched, but there’s mounting evidence to suggest a relationship.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism found that individuals with type 1 diabetes had significantly lower levels of specific beneficial gut bacteria compared to healthy controls.

This shift in microbiota composition, known as microbiota dysbiosis, may influence immune responses, leading to autoimmunity.

A separate study from Cell Host & Microbe highlighted the role of colonic dysbiosis in autoimmune diseases, including T1D.

Researchers discovered that children at high risk for type 1 diabetes showed early signs of gut dysbiosis long before they developed the disease.

This suggests that imbalances in gut bacteria may not just be a symptom but could be an early indicator of developing diabetes.

Daily Lifestyle Factors That May Trigger Dysbiosis

Now, you might be wondering, “How does this happen in everyday life?”

The answer often lies in our modern lifestyle.

High-sugar diets, processed foods, and frequent antibiotic use can easily upset the microbial balance.

Imagine you are a parent of a child with a genetic predisposition to T1D.

Seemingly innocent daily habits like indulging in sugary snacks or taking frequent courses of antibiotics for infections could unknowingly push the gut microbiome into a state of bowel dysbiosis.

Lack of physical activity and chronic stress, which weaken the immune system, can also add to this imbalance.

It is important to understand that everyone’s gut flora is unique.

However, the common thread across studies is that once GI dysbiosis occurs, it sets the stage for chronic inflammation, one of the hallmarks of autoimmune diseases like T1D.

A 2020 study in Nature Reviews Immunology emphasized that the gut barrier’s permeability increases with dysbiosis, which may allow harmful bacteria to leak into the bloodstream, triggering systemic inflammation and potentially autoimmunity.

Can We Predict Type 1 Diabetes Through Dysbiosis?

If dysbiosis is involved in the development of type 1 diabetes, could it be used to predict the disease before it occurs?

This is a growing area of interest in scientific research.

Some studies suggest that children at risk of developing type 1 diabetes show signs of dysbiosis as early as infancy.

For example, the TEDDY study (The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young) has been examining environmental triggers and their impact on T1D.

Preliminary findings indicate that altered gut microbiota patterns may appear long before the first signs of autoimmunity.

While it is too early to declare that gut dysbiosis is a definitive predictor of type 1 diabetes, ongoing research aims to explore this link further.

Could there be a future where a simple stool test could identify at-risk individuals before symptoms develop?

The science is not there yet, but the potential is fascinating.

Is Dysbiosis the Missing Link?

So, is dysbiosis the missing link in type 1 diabetes?

While it is not the sole cause, there is substantial evidence suggesting that an imbalance in gut bacteria could contribute to the development of T1D.

Dysbiosis can lead to immune system dysregulation, inflammation, and increased gut permeability—all factors that can accelerate autoimmune responses. While more research is needed to fully understand this relationship, it is becoming clear that gut health plays a crucial role in autoimmune diseases like T1D.

The key takeaway here is that lifestyle choices impacting gut health could be influencing more than just digestion.

For those at risk of type 1 diabetes, maintaining a healthy gut microbiome through diet, exercise (such as early morning walks to lower fasting blood sugar), and stress management may be an answer to the burning query – how to lower blood sugar naturally, though not a cure.

We still have much to learn, but recognizing the importance of gut health could be a step in the right direction toward better managing or even preventing autoimmune conditions like T1D.

References: