How Pancreatitis Leads to Type 3c Diabetes?

- admin

- November 1, 2024

- 9:39 am

- No Comments

Ah, the pancreas—a humble, banana-shaped organ that most of us do not think much about until it stops working the way it should.

If you have ever experienced the misfortune of pancreatitis, you shall know that this inflammation of the pancreas is not just painful; it can also wreak havoc on your body in more ways than one.

One of the lesser-known but serious consequences of pancreatitis is the development of type 3c diabetes.

Today, BestDietarySupplementforDiabetics team is going to explore how and why pancreatitis can lead to this often overlooked form of diabetes, all while keeping things conversational and (hopefully) a little entertaining.

Article Index:

- What is Type 3c Diabetes?

- The Role of the Pancreas in Your Body

- How Pancreatitis Damages the Pancreas

- The Link Between Pancreatitis and Insulin Production

- Real-Life Stories: Living with Type 3c Diabetes After Pancreatitis

- The Science Behind It: Studies and Research

- Conclusion: Understanding the Relationship Between Pancreatitis and Diabetes

What is Type 3c Diabetes?

You have probably heard of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but type 3c?

It is the less famous (and arguably misunderstood) cousin.

Type 3c diabetes, also known as pancreatogenic diabetes, develops when the pancreas is damaged.

This damage can come from surgery, trauma, or—you guessed it—chronic pancreatitis.

Unlike type 1 or type 2, type 3c diabetes is not about autoimmune destruction or insulin resistance.

Instead, it results from a pancreas that simply cannot produce enough insulin or digestive enzymes.

The Role of the Pancreas in Your Body

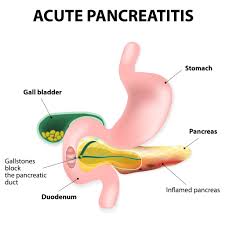

Pancreatitis harms the gland on two fronts: an immediate “autodigestion” hit and a slower, scarring aftermath.

In acute attacks, inactive digestive precursors—zymogens like trypsinogen—switch on too early inside acinar cells.

The pancreas, meant to digest food, starts digesting itself.

That sparks cell injury, swelling, and a systemic inflammatory cascade; in severe episodes, areas of tissue can die (necrosis) and other organs can be pulled into the crisis.

What lights the fuse?

Gallstones are a major culprit; they can obstruct the pancreatic duct and force enzymes backward into the gland.

Alcohol is another—its metabolites and oxidative stress injure acinar cells and sensitize the pancreas to further damage.

Smoking independently raises risk and, combined with alcohol, speeds the march from acute to chronic disease.

Other contributors include very high triglycerides, certain medications, high calcium levels, and genetic variants that alter enzyme activation or ductal secretion.

Chronic pancreatitis is where injury becomes remodeling.

Repeated inflammation activates pancreatic stellate cells—normally quiet support cells—that begin laying down collagen and other matrix proteins.

Over time, this fibrosis distorts ducts, seeds calcifications, and thins the functional tissue (atrophy).

That structural change explains why chronic pancreatitis leads to permanent damage.

Functionally, the fallout comes in two buckets.

First is exocrine failure: too few enzymes reach the intestine, so fats aren’t digested well.

People develop greasy stools (steatorrhea), weight loss, and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies; low bone density can follow.

Pancreatic enzyme replacement eases symptoms and helps nutrition, but it cannot undo existing scars.

Second is endocrine failure: the insulin-producing beta cells are gradually lost.

Glucose control slips, and many patients develop pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c). It differs from type 1 and type 2: insulin needs are common, and because glucagon responses may be blunted, lows can be trickier to manage.

Nutrition, enzyme therapy, and careful glucose monitoring need to work together.

Experts in the field, including David C. Whitcomb, describe advanced chronic pancreatitis by a triad of fibrosis, ductal irregularity with calcifications, and parenchymal atrophy—an anatomical mirror of the functional decline.

Slowing progression means removing drivers (cholecystectomy when gallstones are to blame; strict abstinence from alcohol and smoking), optimizing pain control and nutrition, correcting enzyme deficiency, screening and treating diabetes early, and staying alert to complications in long-standing disease.

How Pancreatitis Damages the Pancreas?

Pancreatitis is not your average inflammation.

It can come in two forms: acute (short-lived) and chronic (long-term).

Acute pancreatitis can often be resolved, but chronic pancreatitis is a different beast altogether.

Chronic pancreatitis causes ongoing inflammation, which leads to permanent scarring and damage to the pancreatic tissue.

This damage impairs the organ’s ability to produce insulin and digestive enzymes.

Dr. David Whitcomb, a leading researcher in pancreatology, has explained that chronic pancreatitis can lead to a gradual loss of pancreatic function.

Over time, the damage extends to the insulin-producing beta cells.

These cells are like tiny insulin factories, and when they get destroyed, your body can’t regulate blood sugar effectively, resulting in type 3c diabetes.

The Link Between Pancreatitis and Insulin Production

So, how exactly does pancreatitis interfere with insulin production?

The pancreas is divided into two functional parts: the exocrine portion, responsible for digestive enzymes, and the endocrine portion, which produces insulin.

When chronic pancreatitis sets in, the inflammation and scarring do not discriminate; they damage both parts of the pancreas.

According to research published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, the destruction of the islet cells (where insulin is produced) is a key factor in developing type 3c diabetes.

When these cells are damaged, your body’s insulin levels drop, making it difficult to keep blood sugar in check.

Additionally, the impaired exocrine function leads to digestive issues, making nutrient absorption difficult and further complicating diabetes management.

Real-Life Stories: Living with Type 3c Diabetes After Pancreatitis

Let’s talk about real people who have experienced this firsthand.

Meet Tom, a 45-year-old who developed chronic pancreatitis after years of gallstone-related issues.

His doctor eventually diagnosed him with type 3c diabetes.

Tom describes it as a “double whammy”—not only does he have to manage his blood sugar levels with insulin injections, but he also has to take enzyme supplements to digest his food properly.

Or consider Maria, who developed pancreatitis due to alcohol abuse in her younger years.

Today, she has type 3c diabetes and has to keep an eye on her diet like a hawk.

Maria says, “I never realized how interconnected everything was until my pancreas stopped working right.

It is like my whole digestive system went on strike.”

These stories illustrate the profound impact that pancreatic damage can have on a person’s life, affecting not just blood sugar levels but overall well-being.

The Science Behind It: Studies and Research

The connection between pancreatitis and type 3c diabetes is well-documented but often misunderstood.

A study in Diabetes Care found that nearly 8% of patients with chronic pancreatitis develop type 3c diabetes within five years of diagnosis.

Another study published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism highlighted that patients with type 3c diabetes often experience more severe complications than those with type 2, partly due to the dual challenge of managing both blood sugar and digestive issues.

One of the biggest challenges in research is that type 3c diabetes is frequently misdiagnosed as type 2 diabetes.

According to Dr. Suresh Chari from the Mayo Clinic, this misdiagnosis can delay appropriate treatment and lead to worse outcomes.

It is crucial for healthcare providers to recognize the unique needs of type 3c diabetes patients, which include both insulin management and enzyme replacement therapy.

Understanding the Relationship Between Pancreatitis and Diabetes

In summary, pancreatitis is not just a painful condition; it has far-reaching consequences that can lead to type 3c diabetes.

The inflammation and scarring from chronic pancreatitis damage the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, making blood sugar management a constant battle.

Add to that the digestive issues from enzyme deficiency, and you’ve got a recipe for a complicated, life-altering diagnosis.

While we cannot change the past, understanding how pancreatitis leads to type 3c diabetes is the first step toward better management and care.

Whether it is through improved diagnostics or a more comprehensive approach to treatment, the more we know, the better equipped we are to tackle this complex form of diabetes.

References: