How Human Placental Lactogen Leads to Gestational Diabetes?

- admin

- November 22, 2024

- 4:14 am

- No Comments

Pregnancy is a beautiful journey, but it is also a time when your body becomes a chemistry lab, with hormones playing the role of mad scientists.

Among these hormonal players, human placental lactogen (hPL) stands out for its role in regulating glucose metabolism.

While hPL is essential for ensuring your growing baby gets the energy it needs, its actions can sometimes go awry, leading to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

In this article, BestDietarySupplementforDiabetics uncover the science behind hPL, exploring how it alters insulin sensitivity, why this change can result in gestational diabetes, and what it means for expecting mothers.

With real-life examples, scientific studies, and a pinch of wit, let’s dive into the fascinating connection between hPL and GDM.

Table of Contents

- What is Human Placental Lactogen?

- Why Insulin Resistance Happens During Pregnancy

- How hPL Triggers Gestational Diabetes

- The Role of hPL in Glucose Sparing for the Fetus

- Real-Life Example: Maria’s Journey with GDM

- Scientific Insights: Studies on hPL and GDM

- Risk Factors That Amplify hPL’s Effects

- The Delicate Hormonal Balance of Pregnancy

- FAQs on Human Placental Lactogen and Diabetes

- Conclusion

What is Human Placental Lactogen?

Human placental lactogen (hPL) is one of the MVPs of pregnancy hormones, secreted by the placenta and playing a crucial role in supporting your baby’s growth and development.

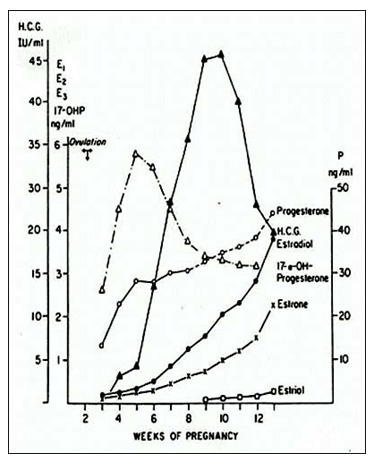

As pregnancy progresses, hPL levels steadily rise, ensuring that both you and your little one are getting what you need—though not always without a trade-off.

Let’s break it down:

- Dual Purpose: True to its name, hPL is a multitasker. It stimulates milk production, preparing the mother for breastfeeding postpartum. But its influence extends far beyond lactation—it directly impacts carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. By tweaking how the mother’s body processes these macronutrients, hPL makes sure the growing baby has a steady energy supply.

- Energy Redistribution: To prioritize the fetus, hPL reduces maternal glucose uptake by the mother’s cells, keeping blood sugar levels elevated. This glucose-sparing mechanism ensures that the baby receives adequate energy, but it also makes the mother’s body less sensitive to insulin. In most cases, the pancreas compensates by producing more insulin. However, if this adaptation falls short, blood sugar levels can climb, potentially leading to gestational diabetes.

While hPL’s effects are vital for fetal development, its impact on maternal metabolism demonstrates how finely tuned and complex pregnancy truly is—sometimes at the mother’s metabolic expense.

Why Insulin Resistance Happens During Pregnancy?

Pregnancy is a time of significant metabolic adaptation, with insulin resistance being one of the most critical changes.

This natural process ensures that more glucose remains in the mother’s bloodstream, ready to be delivered to the growing baby.

While this is a clever evolutionary mechanism to prioritize fetal development, it places extra demands on the mother’s pancreas.

- How It Works: During pregnancy, the body’s insulin sensitivity—how effectively cells respond to insulin—decreases, particularly in the second and third trimesters. This is largely driven by placental hormones, with human placental lactogen (hPL) playing a starring role. As insulin sensitivity drops, the pancreas compensates by ramping up insulin production to maintain normal blood sugar levels.

- The Challenges: For most women, this adaptation works seamlessly. However, in some cases, the pancreas struggles to produce enough insulin to meet the body’s heightened demand. This can lead to elevated blood sugar levels, setting the stage for gestational diabetes.

A study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism highlights that insulin sensitivity can drop by as much as 50% during late pregnancy due to the effects of placental hormones like hPL.

While this change is essential for ensuring the fetus receives adequate nutrients, it can become problematic if the maternal system cannot compensate effectively.

Understanding this balance is key to managing and mitigating gestational diabetes risk.

How hPL Triggers Gestational Diabetes?

Human placental lactogen (hPL) is essential for ensuring your baby gets the energy it needs, but its actions can sometimes backfire, leading to gestational diabetes.

Here is how it happens:

- Reduced Insulin Sensitivity: hPL decreases the mother’s insulin sensitivity, making it harder for her cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream. To compensate, the pancreas ramps up insulin production.

- Pancreatic Overload: While many women’s bodies adapt seamlessly, for some, the pancreas can’t produce enough insulin to counteract the insulin resistance caused by hPL. This imbalance leads to elevated blood sugar levels—a hallmark of gestational diabetes.

- Glucose Sparing Gone Wrong: hPL’s job is to ensure that sufficient glucose is available for the fetus. However, this mechanism can overshoot, leaving maternal blood sugar levels too high, increasing GDM risk.

A study published in Diabetes Care demonstrated that women with elevated hPL levels were significantly more likely to develop gestational diabetes.

This highlights the hormone’s crucial role in managing (or disrupting) glucose metabolism during pregnancy.

While hPL is vital for fetal development, its effects on maternal glucose regulation can make gestational diabetes an unintended consequence of its glucose-sparing actions.

The Role of hPL in Glucose Sparing for the Fetus

Glucose sparing is a critical adaptation during pregnancy, ensuring that the growing fetus receives a steady supply of energy.

At the heart of this process is human placental lactogen (hPL), which orchestrates maternal glucose redistribution.

- The Science: hPL communicates with the mother’s body to prioritize glucose availability for the fetus. It reduces insulin sensitivity, making it harder for the mother’s cells to absorb glucose. Simultaneously, it signals the liver to produce more glucose, increasing blood sugar levels. This mechanism ensures that glucose remains readily available in the maternal bloodstream, ready to cross the placenta and nourish the baby.

- The Catch: While this process is crucial for fetal development, it comes with potential risks. When maternal factors like obesity or pre-existing insulin resistance are present, hPL’s glucose-sparing actions can tip the balance, overwhelming the pancreas and leading to gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

A study in The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology confirms that these interactions between hPL and metabolic risk factors significantly contribute to GDM.

This highlights the delicate balance between ensuring fetal energy needs and maintaining maternal glucose control—a balance that hPL plays a pivotal role in regulating.

Maria’s Journey with GDM

Maria, a 35-year-old marketing professional, was ecstatic when she discovered she was pregnant.

However, during her second trimester, a routine glucose tolerance test revealed elevated blood sugar levels, and she was diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

Her doctor explained that her body’s insulin resistance, driven by placental hormones like hPL, was likely to blame.

Maria adopted a low-glycemic diet and incorporated light exercise into her routine.

By the third trimester, her blood sugar levels were under control, and she delivered a healthy baby.

Maria’s experience highlights how hPL-driven insulin resistance can be managed effectively with proactive care.

Scientific Insights: Studies on hPL and GDM

Research has provided valuable insights into the role of hPL in gestational diabetes:

- Diabetes Care Study: Found a direct correlation between elevated hPL levels and insulin resistance in pregnant women.

- The American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Highlighted that women with GDM exhibited higher concentrations of hPL compared to those without the condition.

- Endocrinology and Metabolism Research: Confirmed that hPL disrupts insulin signaling pathways, increasing glucose levels in the maternal bloodstream.

These studies underscore the importance of monitoring hPL levels and their impact on glucose metabolism during pregnancy.

Risk Factors That Amplify hPL’s Effects

While human placental lactogen (hPL) plays a universal role in pregnancy, certain risk factors can magnify its insulin-resistant effects, significantly increasing the chances of gestational diabetes (GDM).

- Obesity: Excess body fat naturally contributes to insulin resistance. When combined with hPL’s glucose-sparing actions, this can create a perfect storm for elevated blood sugar levels.

- Age: Women over 30 experience age-related declines in insulin sensitivity, making them more vulnerable to the impacts of hPL.

- Family History: A genetic predisposition to type 2 diabetes amplifies the effects of hPL, increasing the likelihood of GDM.

- Sedentary Lifestyle: Physical inactivity further reduces insulin sensitivity, exacerbating the glucose-sparing effects of hPL.

A study published in the British Medical Journal highlighted that women with high hPL levels and these additional risk factors had a significantly increased likelihood of developing GDM.

This underscores the importance of understanding how individual health and lifestyle choices interact with hormonal changes during pregnancy.

Recognizing these risk factors can help expectant mothers and healthcare providers better anticipate and manage GDM risks.

The Delicate Hormonal Balance of Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a tightrope walk of hormonal regulation.

While hPL plays a critical role in ensuring fetal nutrition, it must work in harmony with other hormones like progesterone, estrogen, and cortisol.

When this balance is disrupted, the risk of complications like GDM rises.

Understanding this interplay is key to identifying at-risk pregnancies and implementing preventive measures.

FAQs on Human Placental Lactogen and Gestational Diabetes

Q-1: How does hPL tilt maternal metabolism toward insulin resistance?

A-1: hPL is a placental hormone designed to spare glucose for the fetus. It does this by ramping up lipolysis so the mother relies more on fats, while free fatty acids and downstream signals make muscle and liver less responsive to insulin. The liver also produces more glucose between meals. In most pregnancies that’s adaptive; it becomes problematic only when the mother’s pancreas can’t counterbalance with extra insulin owing to placental hormonal imbalance.

Q-2: If hPL rises in all pregnancies, why do only some develop gestational diabetes (GDM)?

A-2: The difference is β-cell reserve. Alongside promoting insulin resistance, hPL (with prolactin and related placental lactogens) normally nudges the pancreas to grow and secrete more insulin. GDM appears when that compensatory response isn’t strong enough—due to genetic factors, preexisting insulin resistance, or limited β-cell adaptability—so post-meal spikes show up first, followed by higher fasting glucose.

Q-3: Does a higher hPL level automatically mean higher GDM risk?

A-3: Not necessarily. Many studies find that absolute hPL concentrations are similar in people with and without GDM. What matters is the balance between the insulin-resisting effect of hPL and the pancreas’s ability to match it. The same hormonal “dose” can be perfectly manageable in one person and diabetogenic in another, depending on β-cell capacity and background metabolic health.

Q-4: Why is glucose screening scheduled for 24–28 weeks—and what’s hPL’s role in that timing?

A-4: hPL and other contra-insulin hormones climb steadily and are robust by mid-pregnancy. Around 24–28 weeks, their combined effects are strong enough to reveal whether the pancreas is keeping up. That’s why oral glucose testing sits there on the calendar; earlier screening is reserved for those with high baseline risk (prior GDM, obesity, PCOS, strong family history).

Q-5: How does hPL interact with other hormones and lipids to push dysglycemia?

A-5: hPL teams with placental growth hormone, cortisol dynamics, and inflammatory signals to amplify insulin resistance. By boosting lipolysis and altering lipid handling, it increases fatty acid delivery to the liver—fuel that encourages extra glucose output overnight and between meals. When layered on top of preexisting insulin resistance, the overall insulin demand can surpass β-cell capacity, tipping the system into GDM.

Takeaway: hPL is part of a normal placental strategy that reroutes fuel to the fetus by raising maternal insulin resistance. GDM develops when pancreatic compensation can’t match that rising demand. Watching timing (mid-pregnancy), early signs (larger post-meal spikes), and background risks (e.g., obesity, PCOS, family history) helps identify who might need earlier counseling, closer monitoring, and, if necessary, treatment.

Takeaway

Human placental lactogen is a powerful hormone that ensures the fetus gets the energy it needs, but its glucose-sparing actions can inadvertently lead to gestational diabetes in some women.

By reducing maternal insulin sensitivity, hPL prioritizes fetal growth but sometimes at the expense of the mother’s blood sugar control.

Understanding the role of hPL in gestational diabetes highlights the importance of early screening, proactive management, and lifestyle interventions.

While hPL is a natural part of pregnancy, recognizing its impact allows expectant mothers and healthcare providers to navigate these changes effectively, ensuring the health of both mother and baby.

References: