How Autosomal Inheritance Impacts MODY Gene Mutations?

- admin

- November 29, 2024

- 9:16 am

- No Comments

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is a unique form of monogenic diabetes primarily caused by mutations in specific genes.

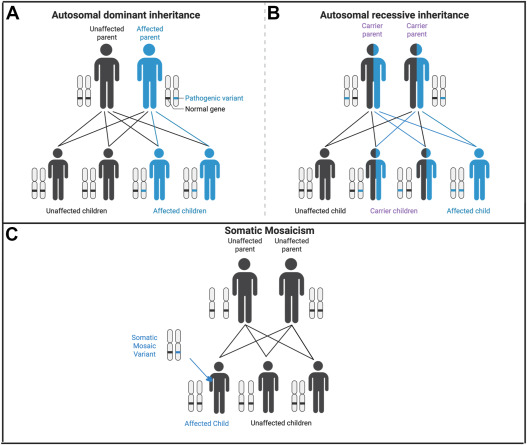

Unlike more common types of diabetes, MODY is transmitted in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that the presence of one mutated gene copy can result in the condition.

This article delves into the mechanisms of autosomal inheritance and its role in shaping the development and progression of MODY gene mutations.

BestDietarySupplementforDiabetics research staff will explore the genetic factors, specific mutations, familial patterns, and the implications for individuals diagnosed with MODY.

Article Index:

- Introduction to MODY and Autosomal Inheritance

- Key MODY Genes and Their Functions

- The Role of Autosomal Dominant Inheritance

- How Autosomal Inheritance Contributes to MODY Onset

- Real-Life Example: A Family’s MODY Journey

- Impact of Autosomal Inheritance on Diagnostic Strategies

- FAQs on Chromosomal Mutations and MODY Diabetes

- Research Insights into Autosomal Inheritance and MODY

- Conclusion

Introduction to MODY and Autosomal Inheritance

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is a rare, monogenic form of diabetes that highlights the powerful influence of genetics on disease development.

Unlike the more common forms of diabetes, such as Type 1 or Type 2, MODY is caused by mutations in a single gene, making it distinct in its presentation and inheritance.

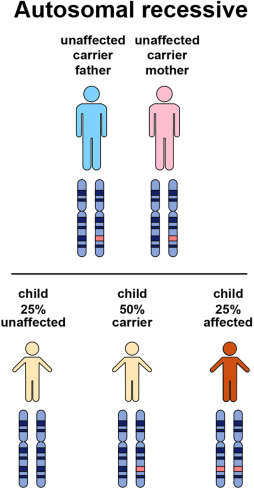

The condition follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that an affected parent has a 50% chance of passing the mutated gene to their offspring.

This predictable transmission makes MODY highly familial, often spanning multiple generations within a family.

MODY’s autosomal inheritance pattern emphasizes the importance of early genetic testing and counseling.

These tools not only aid in precise diagnosis but also help differentiate MODY from other diabetes types, ensuring appropriate treatment.

For example, many MODY patients benefit from oral medications rather than insulin.

By understanding the genetic and familial basis of MODY, healthcare providers can tailor interventions to manage the condition effectively while offering at-risk family members the opportunity for early screening and prevention strategies.

Key MODY Genes and Their Functions

Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is primarily driven by mutations in specific genes (genetic predisposition) that are pivotal for glucose regulation and insulin production.

These include:

- HNF1A (MODY3): This gene is critical for insulin secretion and beta-cell function. Mutations disrupt these processes, leading to glucose intolerance and early-onset diabetes. HNF1A mutations are the most common, accounting for 30–50% of MODY cases, according to the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

- GCK (MODY2): Responsible for glucose sensing, mutations in the GCK gene result in mild, stable hyperglycemia that is often detected incidentally. This subtype rarely requires pharmacological intervention.

- HNF4A (MODY1): This gene influences both the production and secretion of insulin. Mutations can cause progressive diabetes, presenting with more severe glycemic fluctuations over time.

The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern ensures a 50% transmission risk of these gene mutations from an affected parent to their offspring.

Understanding the roles of these genes in MODY provides crucial insight into why the condition manifests early and how it differs from polygenic diabetes forms like Type 2 diabetes.

What Are the Implications of Autosomal Inheritance on MODY Onset?

Autosomal inheritance significantly shapes the onset and progression of MODY (Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young), a monogenic form of diabetes.

Its dominant inheritance pattern ensures that an affected individual has a 50% chance of passing the mutation to their offspring, making family history a critical diagnostic tool.

- Predictable Disease Transmission: Because MODY follows an autosomal dominant pattern, it often appears in successive generations. Families with early-onset diabetes that does not require insulin should be evaluated for MODY, as the condition’s genetic origin allows for precise prediction of who may be at risk.

- Consistent Early Onset: Unlike polygenic diabetes forms, autosomal inheritance in MODY leads to a more consistent age of onset, typically before 25 years. This consistency helps differentiate MODY from Type 2 diabetes, which is heavily influenced by environmental factors.

- Facilitating Early Diagnosis: Autosomal inheritance makes it easier to identify MODY cases through genetic screening of families with a history of diabetes. This early diagnosis enables proactive management and tailored treatments, such as sulfonylureas for HNF1A-related MODY.

The implications of autosomal inheritance on MODY onset emphasize the need for family-focused genetic testing and awareness, providing a pathway for timely intervention and improved outcomes.

How Autosomal Inheritance Contributes to MODY Onset?

The autosomal inheritance pattern of MODY plays a pivotal role in its early onset, typically before age 25.

This unique genetic mechanism explains why MODY is often misdiagnosed as Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

Here is how autosomal inheritance impacts MODY:

- Reduced Genetic Buffering: Since MODY mutations are dominant, a single defective gene copy is enough to impair beta-cell function. This lack of redundancy accelerates glucose dysregulation, leading to early diabetes symptoms.

- Familial Predisposition: With a 50% chance of inheritance, MODY often appears across multiple generations. This familial clustering highlights the importance of genetic screening for early diagnosis and management.

- Mutation-Specific Effects: Different MODY gene mutations, such as in HNF1A, GCK, or HNF4A, result in variable onset and severity, but all are influenced by the autosomal pattern of inheritance.

A study published in Diabetologia emphasizes that recognizing autosomal inheritance patterns allows for earlier interventions and tailored treatments in MODY families, reducing complications and improving quality of life.

Understanding this inheritance mechanism is key to identifying and managing MODY effectively.

Emily’s Diagnosis

Emily, a 22-year-old college student, noticed mild hyperglycemia during a routine health check.

Initially dismissed as stress-related, further investigation revealed a strong family history—her father had been diagnosed with diabetes at 30 and managed it successfully with oral medications.

Recognizing the familial pattern, her doctor ordered genetic testing, which confirmed an HNF1A mutation, diagnosing Emily with MODY3.

Impact of Diagnosis:

With her diagnosis clarified, Emily transitioned from unnecessary insulin therapy to sulfonylureas, which restored her blood sugar levels to near-normal.

Inspired by Emily’s case, her family underwent genetic screening. This identified her younger brother as a carrier of the mutation, though he had not yet developed symptoms.

Early interventions, including regular monitoring and lifestyle adjustments, helped delay disease onset and prevent complications.

This real-life example demonstrates the role of autosomal inheritance in facilitating early detection, enabling proactive management for better outcomes across generations.

Impact of Autosomal Inheritance on Diagnostic Strategies

Autosomal inheritance plays a pivotal role in diagnosing MODY, enhancing precision and streamlining the diagnostic process through:

Family History Evaluation:

Autosomal inheritance ensures a consistent pattern of early-onset diabetes within families.

By identifying individuals with diabetes diagnosed before age 25, healthcare providers can suspect MODY rather than Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

This pattern often leads to earlier and more accurate diagnosis.

Targeted Genetic Testing:

The autosomal dominant nature of MODY focuses genetic testing on specific gene mutations, such as HNF1A, GCK, and HNF4A.

This targeted approach minimizes costs and provides definitive answers about the genetic cause of the condition.

But how does genetic testing reveal MODY gene mutations?

Through advanced techniques like next-generation sequencing (NGS), genetic testing identifies specific mutations responsible for impaired glucose regulation, enabling precise diagnosis.

Cascade Screening:

Testing family members of a diagnosed patient, a process known as cascade screening, identifies other at-risk individuals who may develop MODY.

Early detection enables timely interventions, preventing complications and tailoring treatments.

According to the American Diabetes Association, recognizing autosomal inheritance reduces the mismanagement of MODY, as many patients benefit from oral medications like sulfonylureas rather than insulin therapy.

This process demonstrates the critical role of genetic testing in revealing MODY gene mutations, highlighting how inheritance patterns guide precise and effective treatment strategies.

FAQs on Chromosomal Mutations and MODY Diabetes

Q-1: Why does autosomal-dominant inheritance make MODY show up like “diabetes every generation”?

A-1: With one altered copy enough to cause disease, each child of an affected parent has a 50% chance of inheriting the variant. Because penetrance is often age-dependent, a grandparent may look “diet-controlled,” a parent needs tablets, and a teen develops early hyperglycemia—same gene, different timing. This vertical pattern (grandparent → parent → child) is the pedigree clue that separates MODY from polygenic Type 2 clustered by shared environment.

Q-2: If the mutation is the same in a family, why does severity differ so much?

A-2: Autosomal-dominant doesn’t mean identical expression. Variable expressivity comes from modifier genes (lipids, β-cell stress pathways), copy-number differences near the MODY gene’s enhancers, and life factors (birthweight, sleep, diet, medications). One sibling with an HNF1A change may respond dramatically to tiny sulfonylurea doses; another—same variant—needs modest insulin during stressful periods. The inheritance sets the risk, while modifiers shape the phenotype.

Q-3: Can a child have MODY if neither parent tests positive?

A-3: Yes—via a de novo variant or parental germline mosaicism. In a de novo case, the variant arises in the child; recurrence risk for siblings is low but not zero if a parent has mosaicism (the variant present in some egg/sperm cells but absent in blood). That’s why genetic counseling discusses mosaicism and, if suspected, may suggest targeted testing of additional tissues or relatives.

Q-4: Does it matter which parent passes on a MODY variant during pregnancy?

A-4: Often, yes. Parental origin can change fetal growth patterns. For example, when a mother carries a glucokinase (GCK) variant and the fetus does not, maternal glucose can drive fetal overgrowth; if the fetus does inherit it, growth tends to normalize because the fetal pancreas “expects” the higher set-point. Some HNF4A families show the reverse—infants can be large and transiently hypoglycemic if the variant is transmitted. Same autosomal rules, different perinatal management.

Q-5: How do autosomal rules guide testing and treatment across the family?

A-5: Start with an affected proband; once a pathogenic variant is found, offer cascade testing to first-degree relatives (each has ~50% risk). A precise label reshapes therapy: HNF1A/HNF4A carriers often switch from insulin to low-dose sulfonylureas; GCK carriers typically avoid unnecessary drugs outside pregnancy; HNF1B carriers need kidney and electrolyte monitoring. Autosomal inheritance sets a clear roadmap—who to test, how to treat, and when to plan ahead for pregnancy and long-term screening.

Research Insights into Autosomal Inheritance and MODY

Recent research has significantly enhanced our understanding of how autosomal inheritance shapes the onset and progression of MODY:

- Gene-Specific Risks

Studies reveal that HNF1A mutations are associated with a higher likelihood of early-onset diabetes during adolescence compared to GCK mutations, which often result in mild, stable hyperglycemia. - Predictive Models

Genetic advancements have enabled the development of predictive models that analyze inheritance patterns to estimate the risk and timing of MODY onset in families. These models help identify at-risk individuals early, paving the way for preventive interventions. - Therapeutic Implications

A deeper understanding of autosomal inheritance guides the creation of personalized treatment plans tailored to specific gene mutations. These strategies minimize complications and improve disease management.

For example, a Nature Genetics study demonstrated that family-focused interventions, including early lifestyle adjustments and monitoring, significantly delayed the progression of MODY in carriers.

These insights underscore the critical role of genetic research in improving outcomes for MODY patients and their families.

Conclusion

Autosomal inheritance is a cornerstone of MODY development, determining its onset, progression, and familial patterns.

By disrupting specific genes like HNF1A and GCK, this inheritance mechanism ensures a predictable yet manageable presentation of diabetes in young individuals.

Understanding the genetic basis empowers families and healthcare providers to implement timely diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, improving outcomes for MODY patients.

Final Note: Genetic counseling and early screening remain critical in mitigating the long-term impact of MODY, underscoring the importance of family-based approaches in genetic disorders.

References: