How Alström Syndrome Affects Kidney Function Over Time?

- admin

- January 19, 2025

- 10:24 am

- No Comments

Alström Syndrome (AS) is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by mutations in the ALMS1 gene, affecting multiple organ systems, including the kidneys.

Renal complications in AS usually begin in childhood and progressively worsen over time, leading to chronic kidney disease (CKD) and, in severe cases, end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Studies have shown that AS patients experience early signs of kidney dysfunction, such as proteinuria, nephrocalcinosis, and decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which contribute to long-term renal impairment.

According to research published in Clinical Kidney Journal (2022), nearly 60% of AS patients develop significant renal complications by their teenage years.

As per bestdietarysupplementfordiabetics.com research, “Hypertension and insulin resistance further exacerbate kidney damage, making management challenging”.

Early diagnosis through genetic testing and routine renal function monitoring is crucial for slowing disease progression and improving patient outcomes.

Current treatment strategies focus on managing symptoms, preserving kidney function, and delaying the need for dialysis or transplantation.

Article Index:

- Overview of Alström Syndrome

- Genetic Basis and Kidney Involvement

- Progression of Kidney Dysfunction

- Clinical Manifestations of Renal Involvement

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Management and Treatment Options

- Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

- FAQs on Alström Syndrome and Kidney Function

- Conclusion

Overview of Alström Syndrome

Alström Syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ALMS1 gene, leading to widespread organ dysfunction.

As per a study in Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2020), the estimated prevalence is fewer than 1 in 1,000,000 individuals. Symptoms include early-onset vision and hearing loss, cardiomyopathy, metabolic syndrome, and progressive renal impairment.

The kidney complications in AS often manifest early, contributing significantly to morbidity.

ALMS1 gene mutation also leads to cardiomyopathy.

Genetic Basis and Kidney Involvement

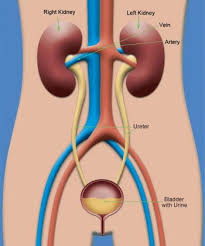

Mutations in the ALMS1 gene, located on chromosome 2p13, are fundamental to the renal complications seen in Alström Syndrome (AS).

The ALMS1 protein plays a key role in the function of primary cilia, which are crucial for cellular signaling, fluid balance, and homeostasis within the kidney.

These cilia help regulate essential processes such as tubular reabsorption and filtration in the nephron.

As per research published in PLOS Genetics (2021), dysfunction in primary cilia due to ALMS1 mutations leads to abnormal cellular signaling, impaired waste filtration, and fluid balance dysregulation.

Over time, these disruptions result in progressive nephropathy, characterized by proteinuria, nephron loss, and declining glomerular filtration rates (GFR).

ALMS1 mutations also affects retinal cells, thereby leading to vision related issues.

Additionally, ciliary dysfunction increases susceptibility to fibrosis and chronic inflammation, further accelerating kidney damage.

Understanding the molecular basis of ALMS1-related renal disease is crucial for developing targeted interventions aimed at preserving kidney function and improving patient outcomes.

Progression of Kidney Dysfunction

Kidney function decline in Alström Syndrome (AS) is progressive and inevitable, often starting in childhood and gradually worsening over time.

As per a study published in Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation (2019), renal impairment in AS typically begins in early life, with most patients developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) by early adulthood.

The study highlighted that the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) declines at a median rate of 15 mL/min/1.73 m² per decade, with males experiencing a faster deterioration compared to females. The progressive loss of kidney function leads to complications such as proteinuria, hypertension, and electrolyte imbalances, which further accelerate renal decline.

If left unmanaged, AS-related renal dysfunction often advances to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), necessitating life-sustaining interventions such as dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Early diagnosis and comprehensive management strategies, including blood pressure control and dietary modifications, are crucial to slowing the progression of renal disease in AS patients.

Clinical Manifestations of Renal Involvement

The renal complications in AS present with several hallmark symptoms and findings:

- Proteinuria: A common early sign, indicating glomerular damage. As per Kidney International (2021), persistent proteinuria accelerates kidney function decline in AS patients.

- Nephrocalcinosis: Calcium deposition in the kidney tissue, leading to tubular dysfunction, is frequently observed in imaging studies.

- Hypertension: A prevalent complication due to impaired kidney function, requiring aggressive management to prevent further renal decline.

- Reduced GFR: Progressive decline in GFR, an indicator of worsening renal function over time.

A study in Clinical Kidney Journal (2022) highlighted that over 70% of AS patients exhibit one or more of these symptoms by adolescence.

Diagnostic Approaches

Early detection of renal involvement in AS is critical for timely intervention. Diagnostic methods include:

- Serum Creatinine and eGFR Testing: Routine blood tests to assess kidney function.

- Urinalysis: Detection of proteinuria and hematuria, which are early indicators of kidney damage.

- Renal Ultrasound: Imaging studies to identify structural abnormalities such as nephrocalcinosis and kidney atrophy.

- Genetic Testing: Confirmatory diagnosis through identification of mutations in the ALMS1 gene.

As per American Journal of Medical Genetics (2021), combining genetic screening with routine kidney function tests enhances early detection rates and facilitates better disease management.

Management and Treatment Options

While there is no cure for AS, effective management can slow the progression of kidney disease. Key treatment strategies include:

- Blood Pressure Control: As per a study in Hypertension (2021), the use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) helps in reducing proteinuria and slowing CKD progression.

- Glycemic Management: Insulin resistance is common in AS; therefore, blood sugar control is crucial to minimize kidney damage.

- Dietary Modifications: Low-sodium, low-protein diets can reduce the workload on the kidneys, as recommended by the National Kidney Foundation (2022).

- Regular Monitoring: Periodic kidney function tests to track disease progression and adjust treatment accordingly.

- Renal Replacement Therapy: In advanced stages, dialysis or kidney transplantation may become necessary. As per Transplantation Proceedings (2022), transplant outcomes in AS patients are generally positive with early intervention.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

The prognosis of kidney disease in Alström Syndrome (AS) varies widely and is influenced by factors such as the age of onset, genetic variability, and the rate of disease progression.

Early diagnosis and proactive management play a crucial role in slowing renal decline and enhancing the quality of life.

As per Nephrology Reports (2021), without timely intervention, most AS patients experience progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) by their 30s or 40s, requiring dialysis or transplantation.

Despite these challenges, advances in nephrology and personalized treatment approaches offer hope for extending renal function and delaying severe complications.

Optimized management strategies, including blood pressure control, dietary interventions, and early pharmacological treatments, have shown promising results in slowing disease progression.

Additionally, ongoing research is focused on developing targeted therapies aimed at addressing the underlying genetic dysfunction caused by ALMS1 mutations.

These advancements provide optimism for future therapeutic options that may improve long-term outcomes for AS patients.

FAQs on Alström Syndrome and Kidney Function

Q-1: How does Alström syndrome lead to progressive kidney dysfunction over time?

A-1: Alström syndrome causes progressive kidney dysfunction through several mechanisms: mutations in the ALMS1 gene impair ciliary function, disrupting normal renal tubular processes and leading to kidney damage.

Metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes further exacerbate kidney dysfunction. Additionally, structural changes like interstitial fibrosis, glomerular hyalinosis, and tubular atrophy contribute to the decline in kidney function.

Q-2: At what age do individuals with Alström syndrome typically experience significant kidney function decline?

A-2: Kidney function decline in Alström syndrome typically begins in mid-childhood and progresses into adulthood. Some individuals may reach end-stage renal disease as early as their mid- to late teens.

Q-3: What are the common renal manifestations observed in Alström syndrome patients?

A-3: Common renal manifestations include proteinuria, indicating kidney damage, hyperuricemia which can lead to gout, and structural abnormalities such as increased kidney echogenicity, nephrocalcinosis, and cyst formation.

Q-4: How does obesity influence kidney function in individuals with Alström syndrome?

A-4: Obesity, frequently seen in Alström syndrome, worsens kidney function by causing increased glomerular filtration rate (hyperfiltration) that strains the kidneys. It also exacerbates metabolic abnormalities like insulin resistance and hypertension, further impairing renal function.

Q-5: What role does hypertension play in the progression of kidney disease in Alström syndrome?

A-5: Hypertension accelerates kidney disease progression by increasing pressure within the glomeruli, leading to damage, proteinuria, and fibrosis. It also disrupts normal kidney blood flow, worsening renal dysfunction.

Q-6: What are the recommended management strategies to slow kidney function decline in Alström syndrome?

A-6: Management strategies focus on controlling blood pressure with medications such as ACE inhibitors or ARBs, managing diabetes to reduce kidney stress, encouraging lifestyle modifications like weight management and exercise, and regular monitoring of kidney function to detect early signs of deterioration.

Conclusion

Alström Syndrome significantly affects kidney function over time, leading to progressive decline and potential renal failure.

The genetic basis of AS, specifically mutations in the ALMS1 gene, plays a crucial role in disrupting normal kidney function.

Early diagnosis through genetic testing and regular monitoring of kidney function are essential for managing disease progression effectively.

Current treatment approaches focus on slowing disease progression through blood pressure control, dietary modifications, and regular medical follow-ups.

Although there is no cure for AS, proactive management can improve the quality of life for affected individuals.

Further research and clinical advancements hold promise for better therapeutic options in the future.

Understanding the trajectory of renal involvement in AS and adopting comprehensive care strategies can help mitigate complications and enhance patient outcomes.

References: