How Sedentary Behavior Impacts MODY Diabetes Risk?

- admin

- December 8, 2024

- 10:21 am

- No Comments

In an increasingly sedentary world, the implications of physical inactivity extend far beyond general health concerns.

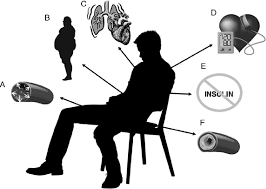

For individuals genetically predisposed to maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY), sedentary behavior may exacerbate risks associated with this monogenic form of diabetes.

MODY, unlike type 1 or type 2 diabetes, results from mutations in specific genes that affect insulin production or secretion.

However, lifestyle factors, such as physical inactivity, can significantly influence its progression and management.

This article by bestdietarysupplementfordiabetics.com delves into how and why sedentary behavior impacts MODY diabetes risk, supported by real-life examples and scientific studies.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction to MODY and Sedentary Behavior

- Understanding Sedentary Behavior and Its Mechanisms

- 2.1. Definition and Examples of Sedentary Activities

- 2.2. Physiological Effects of Prolonged Inactivity

- The Link Between Sedentary Behavior and MODY

- 3.1. Insulin Sensitivity and Sedentary Lifestyle

- 3.2. Effects on Beta-Cell Function in MODY

- Real-Life Examples of Sedentary Behavior and MODY

- 4.1. Case Study: A Teenager with MODY and Sedentary Habits

- 4.2. Case Study: An Office Worker Managing MODY with Inactivity

- Broader Implications of Sedentary Behavior in MODY Populations

- FAQs on Sedentary Behavior & MODY Diabetes

- Conclusion

Introduction to MODY and Sedentary Behavior

MODY diabetes, short for Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young, is like the VIP of the diabetes world—rare, genetically driven, and quite misunderstood.

Caused by mutations in genes such as HNF1A, HNF4A, and GCK, MODY results in impaired insulin production, often rearing its head in young adulthood or even childhood.

While these genetic factors are the primary culprits, lifestyle choices, particularly sedentary behavior, can sneak in as unwelcome accomplices, amplifying the risks and severity of this already challenging condition.

Sedentary behavior—those moments (or hours) spent glued to a screen, sinking into a couch, or logging marathon sessions at your desk—is more harmful than it looks.

It is not just about the extra snack you might grab during a Netflix binge; prolonged inactivity actively disrupts your body’s glucose metabolism, reduces insulin sensitivity, and wreaks havoc on beta-cell function. For those with MODY, this can mean worsened blood sugar control and accelerated disease progression.

In this article, we will dive into the nitty-gritty of how and why being sedentary is bad news for MODY, exploring the science and weaving in relatable real-life examples.

Let us take a closer look at how your daily sitting habits could be tipping the scales in a genetically sensitive situation—pun intended.

Understanding Sedentary Behavior and Its Mechanisms

Let us walk you through aspect in brief:

Definition and Examples of Sedentary Activities:

Sedentary behavior encompasses activities that require minimal physical effort and result in low energy expenditure, typically measured at 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) or lower.

In simple terms, it’s when you’re awake but your body isn’t doing much moving.

Common examples include:

- Sitting at a desk for extended work or study sessions

- Watching TV or streaming endless episodes of your favorite series

- Playing video games for hours on end

- Long commutes spent seated in cars, trains, or buses

These behaviors have become defining features of modern lifestyles.

Technological advancements and urban living encourage sedentary routines, often crowding out time for physical activity that is critical for maintaining metabolic health.

Physiological Effects of Prolonged Inactivity:

Spending too much time in a sedentary state does not just leave you with stiff muscles; it sets off a cascade of physiological changes that negatively impact glucose metabolism, particularly in individuals at risk for MODY diabetes:

- Reduced Insulin Sensitivity: When you’re inactive, your cells become less responsive to insulin, making it harder for glucose to enter and fuel them.

- Increased Fat Accumulation: Sedentary habits encourage visceral fat buildup, a key driver of insulin resistance.

- Impaired Muscle Glucose Uptake: Skeletal muscles, major players in glucose disposal, become sluggish without movement.

A study in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2012) revealed that even short-term sedentary behavior significantly disrupts glucose regulation, underscoring the importance of regular physical activity.

This metabolic imbalance is especially concerning for individuals with MODY, whose insulin production is already compromised.

The Link Between Sedentary Behavior and MODY

Here are the facts:

Insulin Sensitivity and Sedentary Lifestyle:

MODY diabetes, caused by genetic mutations in key insulin-regulating genes, is primarily defined by impaired insulin production rather than insulin resistance.

However, sedentary behavior introduces a complicating factor: reduced insulin sensitivity.

When muscles are inactive for prolonged periods, they fail to efficiently absorb glucose from the bloodstream, forcing the body to produce more insulin to compensate.

For individuals with MODY, this spells trouble.

Their compromised beta-cells already struggle to produce sufficient insulin, and any reduction in insulin sensitivity exacerbates the issue.

A study published in Diabetes Care (2008) showed that sedentary individuals with MODY exhibited greater glucose variability compared to their more active peers, making glucose management significantly harder.

Physical activity, on the other hand, can improve insulin sensitivity by activating glucose transport in muscle cells, a mechanism that is independent of insulin production.

Effects on Beta-Cell Function in MODY:

In MODY, beta-cells are the cornerstone of the problem, as genetic mutations impair their ability to produce insulin.

Inactivity adds to this burden by inducing oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, two factors known to accelerate beta-cell dysfunction.

When the body remains in a sedentary state, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) increase, creating an environment hostile to beta-cell health.

A review in Nature Reviews Endocrinology (2015) highlighted that inactivity significantly amplifies inflammatory responses, further damaging beta-cells in individuals with diabetes.

For MODY patients, whose beta-cell function is already compromised, this leads to faster disease progression and increased difficulty in managing glucose levels.

Breaking periods of inactivity with light physical activity can mitigate these effects and support beta-cell resilience.

Real-Life Examples of Sedentary Behavior and MODY

Case Study: A Teenager with MODY and Sedentary Habits

Emma, a 16-year-old diagnosed with MODY due to an HNF1A mutation, spent most of her time studying and playing video games.

Despite genetic factors being the primary cause of her condition, her sedentary lifestyle led to elevated blood sugar levels and weight gain.

After consulting a specialist, Emma was advised to incorporate light physical activity, such as walking and stretching, during study breaks.

Within three months, her glucose variability improved significantly, demonstrating the role of reduced sedentary time in MODY management.

Case Study: An Office Worker Managing MODY with Inactivity

John, a 35-year-old software engineer with HNF4A-MODY, struggled to maintain stable glucose levels due to his desk job.

Sitting for over 8 hours daily, he experienced frequent postprandial hyperglycemia.

A diabetes educator suggested incorporating 10-minute standing breaks and moderate-intensity walking during lunch hours.

This simple change resulted in better glycemic control, highlighting the adverse effects of inactivity and the benefits of incorporating movement into a sedentary lifestyle.

Broader Implications of Sedentary Behavior in MODY Populations

Listed below are some of the main implications:

Psychological Impact:

Prolonged inactivity is often linked to mental health challenges such as anxiety and depression, which are prevalent among people managing chronic conditions like MODY.

A study in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice (2017) indicated that reduced physical activity is associated with poorer mental health outcomes in diabetic populations, further complicating disease management.

Compounding Effects with Other Risk Factors:

Sedentary behavior compounds other lifestyle risk factors such as poor diet, stress, and lack of sleep, creating a vicious cycle of worsening glucose regulation.

For MODY patients, this interplay accelerates the progression of symptoms, even in the presence of genetic predisposition.

FAQs on Sedentary Behavior & MODY Diabetes

Q1: How does sedentary behavior influence the risk of developing Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)?

A1: Sedentary behavior, characterized by prolonged periods of inactivity such as sitting or lying down, can negatively impact metabolic health by reducing insulin sensitivity and promoting weight gain. In individuals with a genetic predisposition to MODY, these effects may exacerbate the risk of developing the condition. Engaging in regular physical activity can help mitigate these risks by improving insulin sensitivity and supporting healthy weight management.

Q2: Are there specific sedentary activities that particularly increase MODY risk?

A2: Certain sedentary activities, such as excessive screen time (e.g., watching television or using computers), have been associated with higher risks of metabolic disorders. These behaviors often displace time that could be spent on physical activity, leading to negative health outcomes. Limiting such sedentary activities and incorporating more movement throughout the day can help reduce these risks.

Q3: How does sedentary behavior affect insulin resistance in individuals with MODY?

A3: Prolonged sedentary behavior can lead to decreased muscle activity, which negatively affects glucose metabolism. Reduced muscle activity leads to lower insulin sensitivity, prompting the pancreas to produce more insulin to maintain normal blood glucose levels. In individuals with MODY, this can exacerbate insulin resistance, making blood sugar management more challenging.

Q4: Can breaking up sedentary periods help reduce MODY risk?

A4: Yes, interrupting prolonged periods of sitting with short bouts of light-intensity physical activity, such as standing or walking, can improve metabolic health. Even brief activities can enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce blood sugar levels, thereby potentially lowering the risk of developing MODY in susceptible individuals.

Q5: What lifestyle changes can help mitigate the impact of sedentary behavior on MODY risk?

A5: Incorporating regular physical activity into daily routines is crucial. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity per week, as recommended by health guidelines. Additionally, reducing sedentary time by taking short activity breaks throughout the day and engaging in active hobbies can further decrease the risk of developing MODY.

Conclusion

Sedentary behavior significantly impacts MODY diabetes risk by reducing insulin sensitivity, impairing beta-cell function, and contributing to glucose variability.

Real-life examples, such as Emma and John, demonstrate how reducing sedentary time can lead to better glucose control and improved overall health.

While genetic mutations remain the primary cause of MODY, lifestyle factors like physical inactivity can influence its severity and progression.

Understanding the physiological mechanisms and addressing sedentary habits can mitigate the risks associated with MODY diabetes.

By highlighting the importance of movement and active routines, individuals with MODY can better manage their condition and reduce long-term complications.

References: